Reflecting on 4 trial days across two back-to-back weekends in October in Minnesota, I feel most drawn to two out of the eleven searches that I had the honor of judging: a Level 3 Container search, and a large exterior/interior Elite search. These two searches played out like our fintery weather (fall & winter pulling pranks on humanity like a pair of impish Mel Gibsons), punishing you if you didn’t come prepared with every type of clothing you own, layered over you in just the right order so you didn’t sweat to death or freeze to death as time ticked by.

These two searches tell us everything we need to know about what scent work is and could be. These two searches face humans into the mirror of their true goals. These two searches are the fire where the Phoenix is born, they are, to quote the poet Rumi, “the field beyond right & wrong”. The competitor experience (look up the official K9 Nose Work blog for videos and blog posts of some of my competition searches) is quite often a “happening to me” experience (the time ran out on me, the odor wasn’t available to my dog, my dog was distracted, there were no changes of behavior where the hide was). Judging is a “taking account of” experience. Here is my account of what I saw.

Seven Boxes On Benches

How can 1 hide in a box on a bench elude 70% of the competitors?

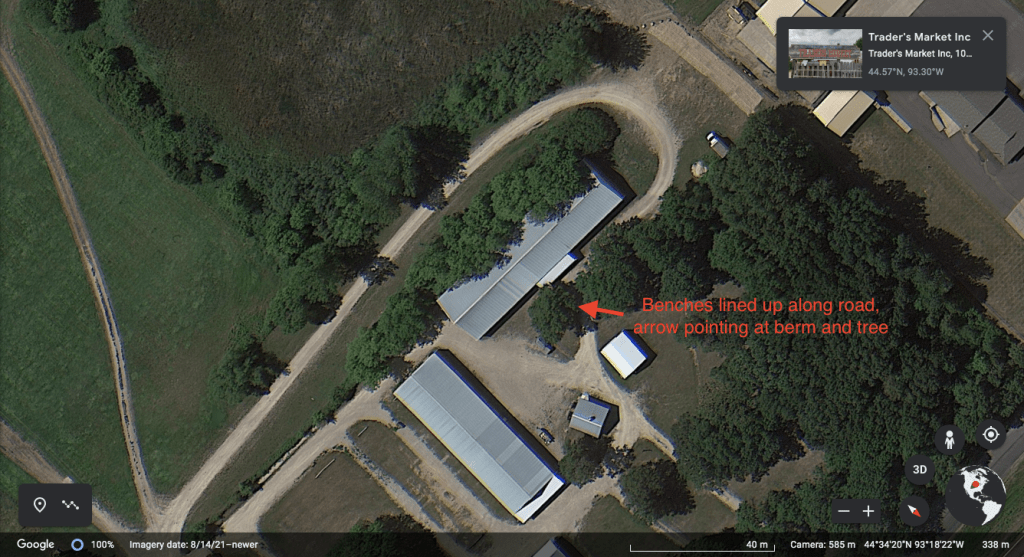

Picture a gravel road, a two foot tall retaining wall, and a grassy berm built up around an old oak tree. Seven wooden benches with seat backs and arm rests are lined up on the gravel road, their backs against the retaining wall. Metal roofed outbuildings surround the benches and the berm at various distances from 30-100ft away. There’s a gap between the 4th and 5th benches where a piece of plywood covers a utility in the gravel road.

Each bench has a white box on it’s seat. Bench number 4 has the one and only hide. Competitors are given a range of 1-4 hides and a time limit of 1:30.

The wind is blowing perpendicular to the line of benches, from across the gravel road, towards the benches and up over the berm with the oak tree. The weather is cool, in the high 40s, the sun is full and the wind is strong.

The start line is set back from the first bench and wide enough to allow easy access to the berm.

The searches can be grouped into three categories: handler led, handler focused on boxes; dog led, handler focused on boxes; and dog led, handler focused on dog.

Handler led, handler focused on boxes searches typically were short leash searches, with the handler controlling the dog to check every box in order. The handler would not allow the dog up on the berm, as that was not where physical access to the boxes was located. Knowing there had to be at least one hide, handlers became more adamant that the dog search the boxes as time ticked away, resulting in heavy focus on the last three boxes where the odor collected – dogs might also leap up on one or more of the benches as the handler’s focus on boxes intensified.

The outcome of these searches was mostly false alerts on one of the last three boxes, or running out of time. Notably, most dogs were not actively sniffing the boxes where false alerts were called, rather they were standing on the bench seats looking at the handler, or showing odor collecting on the bench, maybe frustratedly poking or pawing the box).

Dog led, handler focused on boxes searches looked like it sounds: dogs were given the lead to show where they wanted to go, but handlers stayed firmly in front of the benches where physical access to the boxes was. The dogs in these searches showed strong behavior at the edge of the berm near the start line, with a change in energy focused in the direction of the big oak tree. These dogs also showed strong changes between benches 4 and 5, focusing their interest around the plywood and on the retaining wall. These dogs showed little desire to physically check the boxes.

Some of the handlers in this category gave the dog their full length of leash, allowing movement up the berm, behind all of the benches, but then switched to a handler led, box-focused search with similar outcome as the first category of teams.

Some handlers in this category maintained leash control over their dogs and decided not to follow the dog further away from the benches than the leash would allow, but also did not make a change to a shorter lead, nor did they switch to box presentation/focus. One or two of these teams found the hide in box 4.

Dog led, handler focused on dog searches were the exception – numbering two, maybe three (including the dog in white) teams. The distinction here is that the handler followed the dog up the berm, to the oak, over to a nearby building, back to the gap between benches, out across the gravel road, and back in to the middle three benches where the dog traced, bracketed, then energetically focused on box 4.

What does it mean that the most successful teams were the “dog-led, handler focused on dog” teams? From my vantage point, these competitors used the dog as their window into the reality of the movement of odor, and behaviors they saw in the dog convinced them to stay the course.

I observed some typical behavior in humans and dogs that was only present in the categories of teams where handlers focused on boxes:

Box-focused handler behaviors: opposing the dog’s movements by pulling on the leash or gesturing to get the dog to change focus; repeating the search cue; saying things out loud, like “you’re not working” or “hurry up and find it, we’re running out of time”.

Post-search, saying things like, “well, that sucked!”, “he usually loves containers”, “how many did we miss?”

Dog behaviors of the box-focused teams: trying to pull the handler up the berm, trying to work the ground between benches 4 and 5, stopping to keep the handler from pushing them past the area of strongest odor, looking at the handler more frequently, poking at every box, climbing on benches where odor collected and pointing nose where odor was coming from.

Objectively, the teams that did not find the hide were made up 100% of dogs who attempted to work odor – no dog exhibited dereliction of duty. When met with opposition, these dogs attempted to connect with their handlers, but the majority of handlers responded by commanding the dogs to “find it” and attempting to guide the dogs’ focus back to the boxes. In one case, a handler confirmed that she did not see any of her dog’s behavior changes in the gap between benches, nor did she see her dog pointing back to odor from the 5th bench.

To be clear, the other container search I judged was a two hide search with an upside-down ‘V’ of boxes where many teams passed regardless of the category they fell into. The Bench container search stood out for this very reason. Just as the weather in the days leading up to the trial had swung from 80 degrees to 25 and snowy, prompting me to be ready for anything, the bench search presented “weather” that many teams weren’t prepared for – and some tried to actively disbelieve even as it was freezing over their chances of success.

The Tree of Odor

Elite is a curious beast. According to the progression from NW1 to NW3, searches become more complex via the addition of hides, the placement of hides, increases in area size or object numbers, and additional handling challenges like clearing space and calling finish. NW3 typically has between 8-10 hides across six searches. Elite typically has about 16-20 hides across four searches. Most competitors prefer Elite to any of the lower levels. Is it because of the increased challenges of this advanced level? Let’s look at the facts of a search from one of the Elite days I judged:

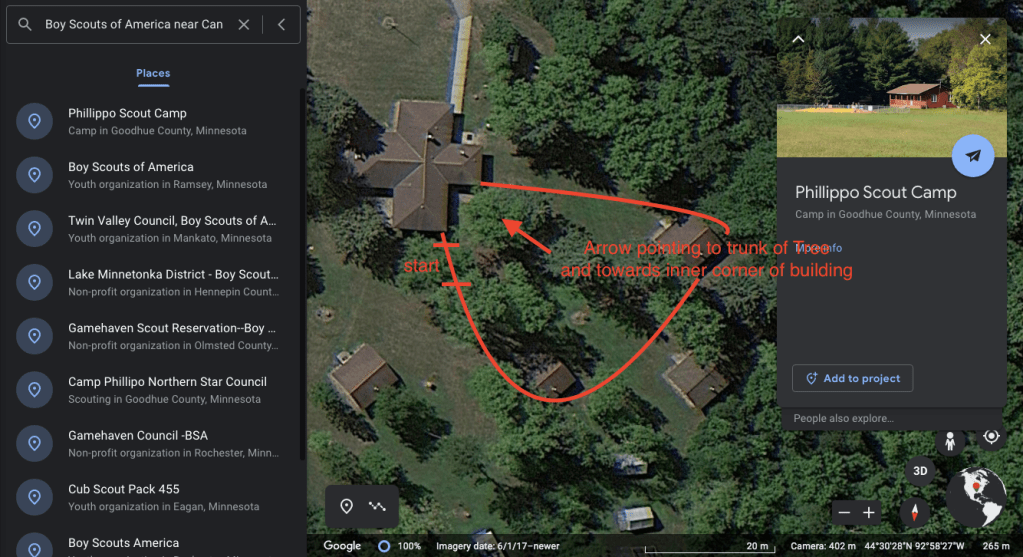

This 5 minute, 5 hide search included a large grassy area between a lodge building and two cabins. A few mature trees dotted the space, along with a line of stumps and caged saplings closer to the cabins than the lodge (stumps, google, the image should show fewer trees and more stumps). The cabins were simple, one room spaces with stacks of chairs, folding tables, and wood stoves. Competitors were given a range of 3-5 hides and were in charge of opening cabin doors to search within.

The start line began at a corner of the lodge building and stretched out about 15 feet, facing competitors at one of the mature trees.

Each cabin had 2 hides: a hide in a stack of chairs and a hide on a table. The 5th and final hide was around 6ft high in the bark of the tree closest to the start line, and close to the lodge building (two walls forming an inner corner were included in the area).

Temps started in the 50s and went up from there. Clouds and low morning sun gave way to clear skies and lots of high, hot sun. Wind was strong and gusty.

For the competitors who searched in full sun, the tree hide was a puzzle in the truest sense. Puzzle pieces of odor were available to gather far and wide throughout the search area, but not in a linear fashion where each piece neatly fit together in completion of the puzzle. More like each piece of odor info was just a piece, until the right piece was discovered and everything else suddenly fell into place.

Many competitors would not risk permitting their dog sniffing trees, stumps or fallen leaves, and promptly moved them on from each puzzle piece of odor. Some competitors were more comfortable with the natural objects, but seemed to treat each sapling cage and tree as a binary decision: source odor or no source odor.

Complexity Doesn’t Pay

Why would handlers have little interest in a complex odor puzzle at the second highest level of NACSW competition?

It could be related to concerns over time and points. Since every hide is worth the same points, you might feel very silly spending 5 minutes searching for 1 hide when you could have used that time to find up to 4 other hides. It could be a lack of practice searching blind and observing the dog solving complex problems. Many people may believe it’s best to practice “hard” hides non-blind and to manage the dog’s efforts and response so the dog can “successfully” find the hide and be rewarded.

We might never know the root of the problem with finding the tree hide, but something will have to change with the way humans and dogs communicate or teams will continue to leaf this type of hide behind.

Opposites Detract

There is a moment that occurs in searches like the Tree search, where a handler has decided that further effort from the dog will be fruitless. This is typically the moment the dog is closest to advancing towards a solution to the location of the hide. As the judge, I responded to one handler’s finish call with, “you can pay your dog!” As she ended the search and relaxed herself, the dog promptly dragged her to the tree and clamored up towards the source. Other searches were ended as the dogs were casting back and forth in the odor cone and staring at the tree, ready but for the reluctance of their handlers to believe the puzzle was nearly solved.

How can a handler’s interpretation of the dog’s behavior be so far from the dog’s own experience?

Maybe we just need to branch out and expand our patterns of communication. Adam Robinson says that the most important phrase to look out for when attempting to understand a complex situation is: “that doesn’t make sense.” Most people reject information that doesn’t make sense, but in a complex situation, what doesn’t make sense happens to be the very thing that will lead you to a solution.

It takes a lot of time and practice to learn to embrace communication that doesn’t make sense – maybe more time than some people want to invest – but, there are little victories to be had along the way. Instead of being surprised by the presence of a complex hide like the Tree hide, you might be able to tell that your dog is working odor from a hide you haven’t called yet. Maybe you’ll be able to tell that your dog is outlining the edges of the odor cone with his pattern of movement and drawing a “target”, within which is the yet-to-be-found hide. You might even be able to tell which direction your dog thinks the odor for this hide is coming from. There’s so much potential understanding before the indication and the alert call – so much opportunity for success.

Odor-Synthesis

The process of turning a dog’s searching behavior into a human’s understanding of the presence of odor – where it’s collecting, how it’s moving, and where the source of the odor is located – could be called odor-synthesis. A few teams’ searches were powered by this process in the Tree search, resulting in all 5 hides found. Common among these teams were handlers who let the dogs lead. These handlers did not reject the communication from their dogs that “didn’t make sense”. These handlers allowed the dogs to push beyond the search boundaries, to investigate the leaves, the ground and the sapling trees, they allowed the dogs to pick up odor, lose it and pick it up again. As the dogs approached the final sniffs of the puzzle, these handlers either understood the purpose behind their dogs’ movements and communication or they went on faith. Indication or not. Alert or not. These handlers and dogs were already successful many times throughout the search.

Competition: Waa Hoo Good God Ya’ll What Is It Good For?

The 7 Box search and the Tree search are the best of what competition has to offer. To have one or two searches like these per trial is a gift from the scentiverse! If more trial searches were complex and required true connection and understanding it would be a lot easier for handlers to invest time and effort in mastering a dog-led, handler-focused-on-dog approach to searching.

As a judge (and a former Certifying Official) I rarely see a competitor’s search in terms of the final outcome, the score or the time. I see the search as a series of opportunities for connection and understanding. If you get a score sheet from me, you’ll often get a running commentary of these many opportunities as I see them. Any search where you are flowing in the energy of connection with your canine partner – even just once – is a win!

Next time you enter a trial, prepare yourself for the possibility of receiving communication from your dog that doesn’t make sense. Welcome that communication. Be patient, don’t reach for meaning. Maybe you can see your dog is clearly in odor, but you’re not sure if he’s near a hide or if there even is a hide. Relax and stay with what you know: he’s in odor. Keep your connection and let him reveal more of what he knows. The more he shares with you, the more you’ll know.

As a judge, I walk away from a trial without ribbons, scores or placements. That makes it easy to walk away with just the experience of taking account of what happened in every search I observed. As a competitor, prepare yourself to walk away with just the experience of flowing in the energy of connection with your dog (you can take the ribbons home, too, if you get them!). That is what matters most, that is what you want more of in all of your future searches.

Happy Sniffing!

This post is just what I needed to read going into a trial this weekend. “The search as a series of opportunities for connection and understanding”, alert or not.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am grateful for every time I’ve watched you & Zest (or Sasha) connect and understand each other. There was a magical moment not too long ago in the frigid cold in Shoreview that a few of us had the honor to watch. It is one thing for a human to skillfully convey what they want an animal to do, it is something entirely different to watch a human skillfully receive a dog’s communication and be in service of what that dog wants/needs. It is a deeply enjoyable exchange to behold. Thank you!

LikeLike